ADHD in girls is severely underdiagnosed

A person with ADHD often does not close browser tabs in fear of forgetting something important. They may also just forget to close any tabs at all. This is an extreme case.

December 14, 2020

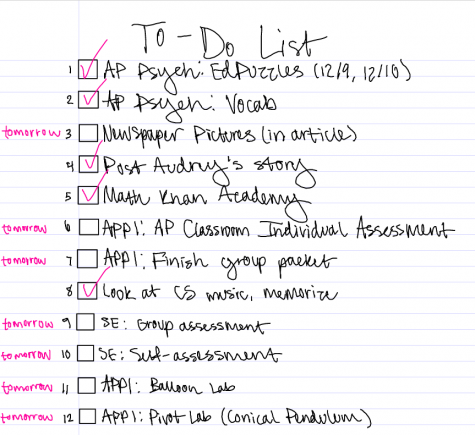

Over the summer, I had to take some e2020 classes for credits that I hadn’t had room for in my schedule junior year: health and economics. I expected to get the classes done early, so that I could enjoy the rest of my summer. So, I sat down, and I tried. I watched the videos and found myself drifting off in thought in the middle of them. I’d have to rewatch and rewatch and rewatch and rewatch again. If something was supposed to take me one hour, it would take me two. I began procrastinating heavily on my work for what felt like no good reason at all. I knew I had to get it done, but I’d wake up at nine and start at three, while spending that entire time obsessing over the work. I would constantly repeat “I have to do it” over and over in my head for hours at a time until my stress levels were so high I had to get up and do it. This wasn’t new. I’d been struggling with menial tasks such as these for years… but why?

Five months later, I’d have my answer: at age 17, I was diagnosed with ADHD, or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

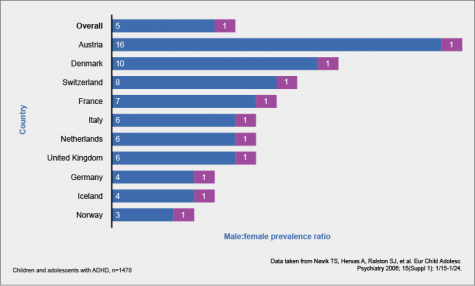

The average age of diagnosis for mild ADHD alone is 7 years old, and the more severe, the earlier in life the diagnosis, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. So why, then, was I diagnosed a decade past the usual benchmark for mild ADHD? As it turns out, ADHD in girls is chronically underdiagnosed. In fact, boys are nearly three times more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than girls are, and it’s been estimated that about 50-75% of girls with ADHD have “slipped through the cracks”— but is this due to ADHD being less prevalent in girls, or is it because of something else entirely?

According to an MHS graduate with ADHD who would like to remain anonymous, referred to hereafter as Jane, “From the time I started having problems to the time I got diagnosed, five years [went by]. It shouldn’t have taken five years… I think if I was a boy and I showed ‘typical’ symptoms I would have been diagnosed immediately, but because I was a girl they looked for everything but ADHD.” She’s not alone. Another MHS student with ADHD who also wished to remain anonymous, referred to hereafter as Mia, shares similar feelings: “I think that if my pediatrician wasn’t a specialist in [ADHD] in children, I never would have been diagnosed. If my mom didn’t ask him about [my issues] I would never have known I had [ADHD].” Social expectations and norms play a massive role in whether or not a girl will be diagnosed with ADHD.

There are three main types of ADHD: inattentive, hyperactive, or a combination of both. With the inattentive ADHD type, a person has a harder time focusing, forgets things frequently, daydreams often, has issues remaining organized, and often finds themselves bored. Those with the hyperactive type also have trouble focusing, but in a different way— they have an extremely difficult time sitting still, have issues completing schoolwork on time, and frequently blurt things out without meaning to.

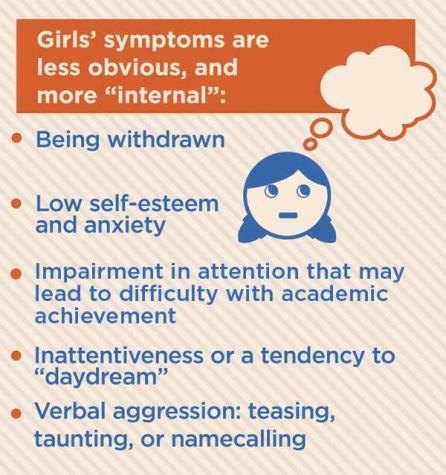

Girls, when diagnosed, are much more frequently diagnosed with the inattentive type, and boys are much more frequently diagnosed with the hyperactive type. And doesn’t that make sense? If a boy with ADHD is running around and disrupting the classroom, he’s going to be flagged for potential ADHD much faster than a talkative little girl, especially if girls are already expected to be sociable. A University of Washington study found out that not only do boys tend to have a wider variety of typical ADHD symptoms, their symptoms also tend to manifest in a more extreme manner. “There is a biological difference,” Jane says. “With girls, it’s such a different manifestation of symptoms and it comes out so differently. We have to go through so many options before you can get to ADHD with a girl. With little boys, when they are hyper, [ADHD] is the first thing the doctors throw out.” Combine that with the fact that women are usually expected to “have it together”— be organized, be in control, be on top of things, be on time— so they develop coping mechanisms without realizing they’re coping mechanisms, and you have disaster brewing. But it runs even deeper than that.

Much like me, Mia also noticed pretty early on that the way she learned in school was different from the other kids— “I was 10 years old. I distinctly remember in the months before my diagnosis with [ADHD] that we were learning long division at my school, and I could not figure out how to do it,” Mia said. “I knew in my head that it was a simple concept, but I couldn’t understand it.” Our symptoms were both missed by our elementary school teachers. She had access to a specialist, and I did not. Although I would be diagnosed seven years later than she was, we both first noticed something was off within just one year of each other. We aren’t isolated examples, either, and there’s a reason for that. In a 2004 survey conducted just one year after we were both born, 58 percent of the general public thought that ADHD was more prevalent in boys. In teachers, the numbers were even more dismal— a shocking 82 percent of teachers thought that ADHD was more prevalent in boys than girls, and four in ten teachers reported having more difficulty recognizing ADHD symptoms in girls. That’s a huge problem, because teachers are an incredibly important first detection source.

In fact, this is even worse than it initially appears, because girls with ADHD are much more likely than their non-ADHD counterparts to struggle with other mental and physical health problems. When two or more disorders are present in a patient, it’s called a comorbidity. A study conducted by the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry found that women with ADHD are much more likely than men with ADHD to have comorbid disorders. A University of Toronto study found that 36% of women with ADHD also had generalized anxiety disorder, 31% had major depressive disorder, 39% had had substance abuse problems in the past, and 46% had seriously considered suicide. If a girl with ADHD remains undiagnosed and untreated, that can spell out harmful and potentially deadly consequences for her later in life, all because the people around her missed the signs.

No matter the gender, having ADHD is debilitating and frustrating. It’s often mistyped as laziness, a lack of motivation, ditziness, or even stupidity. The stigma is both intense and incredibly harmful. “[ADHD] has become something that people want to say they have as a ‘funny’ excuse for why they’re disorganized or stressed out,” Mia says. “It’s actually very difficult to live with, and can honestly be so draining and disappointing. For example, really setting your mind to something, working your absolute hardest to finish it, and still not being able to finish it because of the way your brain is wired [is] absolutely devastating.” Jane agrees: “Most of my college life, my parents have called me lazy— and I’m not. That word is harmful because it makes you feel like you can’t do anything. It’s not like that, and it almost makes it worse. ‘Power through. Sit down and do it!’ I would if I could. The issue is that I can’t. It’s like telling someone that’s been shot to put a bandaid on it.”

The best way that I can describe going through life with ADHD is like this: all of your friends can do backflips. Effortlessly. You watch them all backflip everywhere, all the time, and they ask you to join them. What you don’t know is that you’ve had vertigo all your life— you’ve learned how to function with it, and you never talk about it because you don’t know that none of your friends have it, so you’ve just come to believe that everyone is naturally dizzy. Then, when you try to do a backflip, you can’t. You try and you try, you practice as much as is physically possible, but you’ve never been able to backflip. People ask you why you aren’t trying hard enough, and you reply that you are, you just… can’t do a backflip, and you don’t know why. Naturally, people keep coming to the conclusion that you’re not trying hard enough anyway, or that you’re just dumb. Then, you finally go to a doctor, and your doctor tells you, “Oh, silly, you’ve been seeing things upside-down your whole life; of course you can’t do a backflip!”

The analogy is absolutely ridiculous, but that is exactly what it feels like. To not be able to focus for more than ten minutes at a time is upsetting at best. Being unable to start tasks is equally saddening as it is maddening. At my worst, I’ve spent three weeks straight thinking about an assignment every single day before being able to actually force myself to do it. It carries over into things as simple as being able to clean my room or make my lunch, or into things as important as college applications. The best way I’ve seen it described was with just two words: “chronically overwhelmed”.

Teachers, please be as understanding with your students as you possibly can. You really do never know why a student may be unable to meet deadlines— sometimes, the students themselves don’t know. Educate yourselves on recognizing symptoms of ADHD in both boys and girls, because you very well could be the stepping stone to getting a child help years in advance. Parents, your child with ADHD is not lazy or unmotivated, they’re struggling to get through life on “hard mode.” Be kind to them and tell them you love them. If you’re friends with someone with ADHD, tell them you’re proud of them for what they’ve accomplished, even if they have three thousand missing assignments. They need to hear it, because they’re doing the best they can. And, above all, if you identify with anything I have discussed in this article above, it may be a good indicator that you have ADHD. Self-diagnosis is not the answer, as it frequently leads to misdiagnosis and/or causes further potential problems down the line. Don’t jump to any conclusions. Talk to your doctor, a psychiatrist, or a psychologist. Remember, you are not stupid, you are not lazy, and above all, you are not alone.